——-

Eschatology

by Megan Dickson

Life took us to the edge of the known universe

this brink, this precipice, on a red dirt plateau,

all rust-verged and jagged,

like a tear in heart tissue,

like broken bone projecting through soft skin.

skin, bone, sinew often don’t break cleanly

so there, on that terrifying cliff,

we looked out into the blackness

and saw that it was our own

dotted with infinite, swirling stars,

nebulous arms of our galaxy, folded across

that night, that nothing. we realized

the instant we stepped to the fathomless limit

all the light we carried in our core could somehow

save us, from this end. So into the starry,

inky ebony we leapt, being careful to be

sure that we crossed over the boundary between

everything we’d known, into every

night we’d ever feverishly dreamed.

this jump, this real act of

self-preservation flung us into

the heart of the unknown cosmos

and there we were to greet ourselves

at the gates of our unknowing.

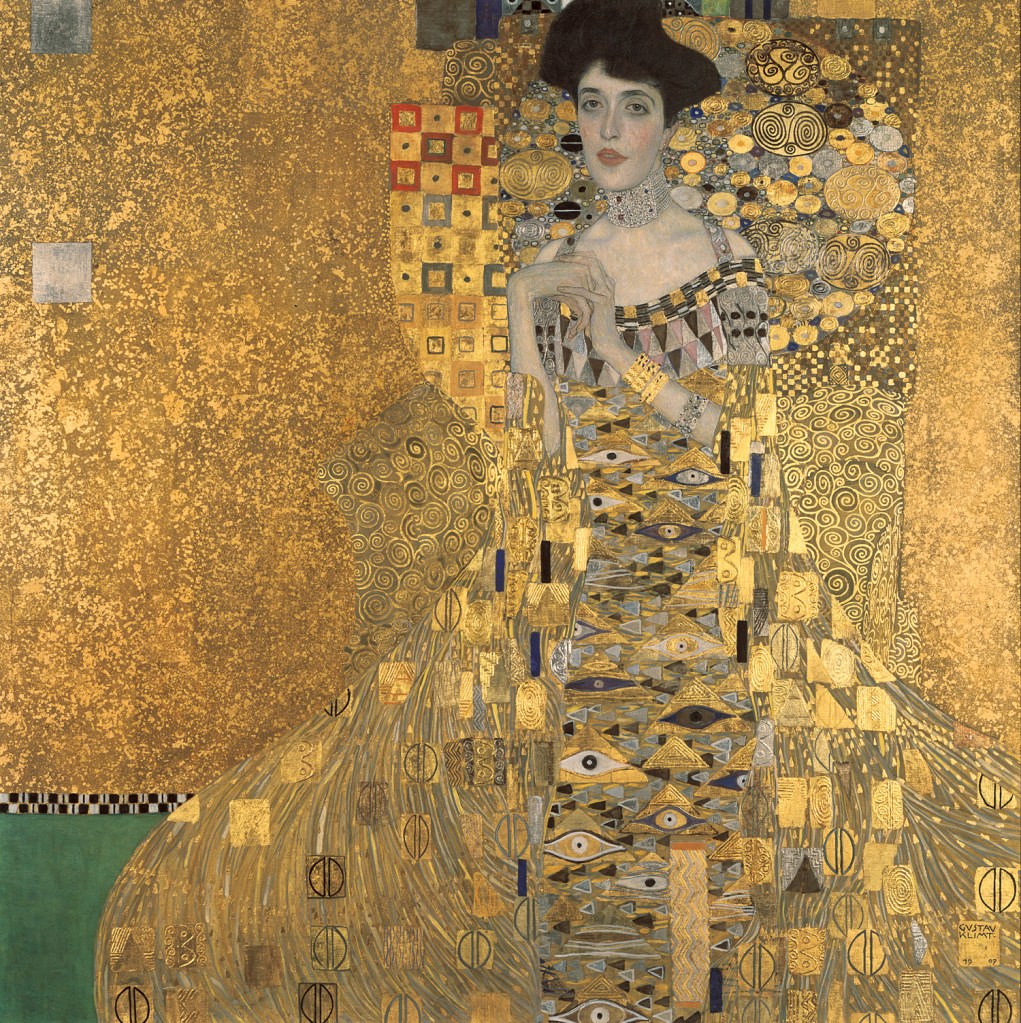

we opened the tiny, golden latch on the

impossibly large, swinging metalwork gate,

stepped slowly, quietly over the threshold of

revelation, everything open and waiting

for us in that pitchy gloam still had

to be sensed– felt, touched, tasted, smelled–

not physically, but by the fingers of

the formerly known soul that now

bore this greater knowing. this

was not the end but the beginning.

a larger excursus on the limitless

infinite than we had previously

known. we’ll never know if there

was only one way to this beginning–

the ledge, the leap, the jump–

our tiny, finite, blink of a guess gives us

the idea that, no, there are

many precipices, many pinnacles, many paths

to the infinite edges of the unknown into

new reaches of galactic consciousness–

seeing and knowing more than we

could possibly have imagined yesterday

——-

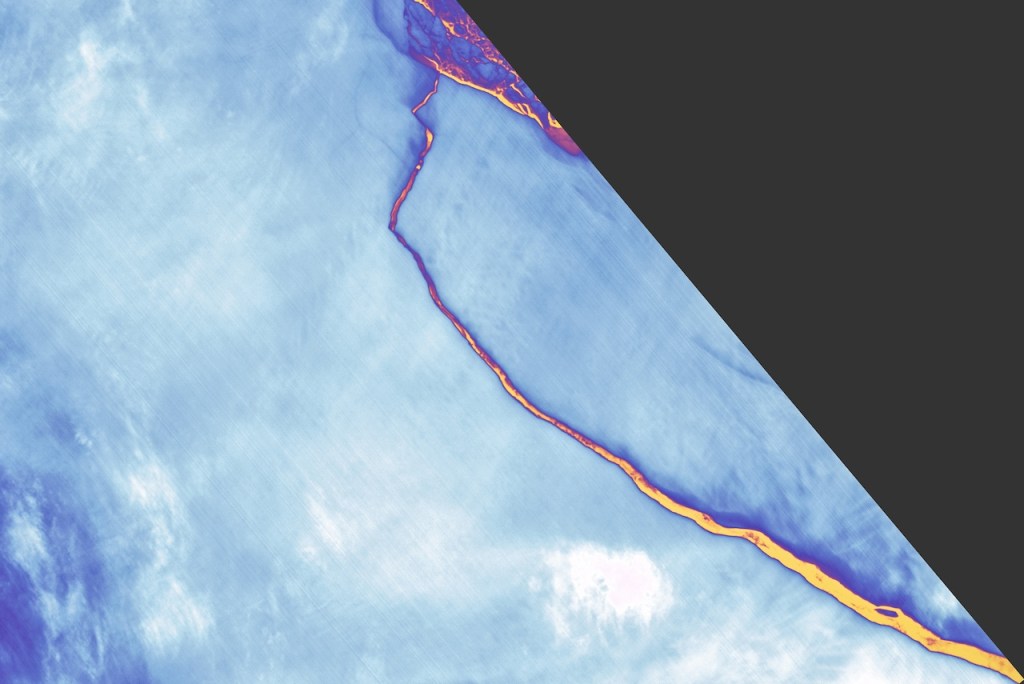

What will happen when there is no ice left in our house? What will the warming Earth mean for humans and animals? Now, nearly twenty years from some of my most intense life experiences, travel, and living in Alaska, I finally realize that the difficulty with this moment of continuing glacial recession is that it is so very difficult for humans to push past their one-hundred-year lifespans to see beyond to the systems that shape not only our now, but our future.

I’m the first to raise my hand and express that this kind of complex information is difficult for the lay-person to process. So how do we make science, scientific facts, and continued scientific hypothesis and discovery on climate change more bite sized, more commonplace, more palatable. The ignorant me doesn’t have a ready answer for this.

Will we overheat and roast as the seas engulf us before we grasp the stunning reality that we need to move from believing that humans can harness Earth and her resources rather than humanity taking more careful notes on how Earth regulates her own systems?

Are we at the 911 phase of this journey? I scarcely think anyone knows. This summer, 2024, has felt hotter than ever. However, feelings don’t really translate into hard scientific evidence. But my “feeling” is backed up by science. July 21, 2024 was the hottest day ever recorded on planet Earth.1

——-

Fanning the yellowed pages under my thumb, the book fell open easily in my hands to the front inside cover. Plastered under a handwritten note was a sticker of a galaxy spiraling in a sea of black, and under its outstretched arms were printed the words, “Ex Libris Kenneth A. Farnsworth.” From the library of my father. He had been the one who scrawled the message above the sticker, “Mom, with love and gratitude for turning me on to this ‘good stuff’.”

Tenderly, I traced the edges of the sticker, and drew my fingers across the fading ink. This small volume was an important relic from my grandmother’s life, a testament to her love of the written word, to the way she not only relished poetry and prose but had also passed this love on to her children and grandchildren. I thought that the book looked centuries old, an age cracked spine and what looked like a hand stitched binding were beginning to peel apart leaving bits of cheese cloth, paste, and leather showing in between. The worn leather exterior bore the title, stamped in gold ink, One Hundred and One Famous Poems. The copyright read Riely & Lee 1958. I guess relic, old, and antique were relative terms.

For instance, I had mistakenly assumed that ideas surrounding the greenhouse effect, and global warming were part of “new science,” or discoveries made recently relative to my lifetime. The reverse is true. Some of these calculations dated back over a century which makes them almost archaic in my humble perspective. Some of the poets in Grandma’s book– Dickinson, Browing, Emerson, Whitman, Longfellow, Wordsworth– had lived during the time when the first scientific theories about what is now termed the “natural greenhouse effect” were being developed. Englishman John Tyndall is credited with the discovery of greenhouse gases in 1859. He drew a simple comparison, “Just as a dam causes a local deepening of the stream, so our atmosphere, thrown as a barrier across the terrestrial rays, produces a local heightening of the temperature at the earth’s surface.” This wasn’t new science it was old news.

On page 81, Lucy Larcom’s poem titled, “Plant A Tree,” sounded like a worthy credo for an early American environmentalist. She had died just one year before Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius began testing his theories that coal burning was changing the character of earth’s atmosphere. Larcom wrote, “He who plants a tree… Plants a hope.” In 1894, a year after Larcom’s death, Arrhenius hoped to determine the effect on earth’s climate in the unlikely event that greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide emitted from coal burning ever doubled. His conclusion: if the greenhouse gases doubled, earth’s temperature would rise.

So if basic climate science isn’t new, why has it taken such a long time for humans to perceive, address, or pay attention to these warnings from scientists? The answers are certainly multi-layered: the relatively short time-span of human life, the heated politicization of climate change, the fact that scientific knowledge is not based on speed but on thoughtful interrogation, the fact that we know that Earth has experienced many climate epochs and mass extinctions in its deep past. Climate scientists including glaciologists, often ask very specific questions of climatic change in very narrow systems. Another reason may be that it can be very difficult to determine when humans should intervene in their environment.

In fact, an article in The Atlantic2 this July, offers some insight and ideas about human intervention into glacial preservation, in short, geoengineering. Ross Anderson interviews Slawek Tulaczyk about his projects on Thwaites glacier in Greenland and on the Western Antarctic ice sheet where he has come to believe that one of the only ways that ice, and perhaps Earth, can be saved from ‘catastrophic’ sea-level rise is to give humans more time to grapple with climate change; therefore, Tulaczyk proposes that humans attempt to stop ice sheet from floeing. His hypothesis and process go well beyond all geoengineering feats that have been attempted on Earth this far. In lay terms, Tulaczyk suggests that we pump water out from underneath large glacial ice sheets in hopes that they will readhere to the underlying bedrock. Tulaczyk believes that humans could keep massive ice shelves intact, and in essence, keep them from separating, melting, and causing sea-level rise.

There on my bed, a weird quantum meeting took place. I imagined Robert Frost listening to these glaciologists, then returning home to send the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), President Jim Skea, these famous lines,

SOME say the world will end in fire,

Some say in Ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To know that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

Fire, ice, ice, fire. From first-hand Northern climate immersion, I would still have to go with the first. I’d say fire.

——

Two days after my grandmother’s funeral, my fingers brushed the soft sheen of one silk square of quilt. Bright mauve lilacs, butter daffodils, and blush sweet peas undulated across the small cubes of fabric. I drew a cubed piece of leopard print fabric to my nose, hoping to catch even a faint breath of her. A gaudy half-moon of colorful Klein blue silk shone in front of me masking the neutral brown tones of the living room carpet in my parents’ home in Duchesne, Utah.

She would have worn any one of these silk creations anywhere. That was the best part. Sure grandma had the shirts that were reserved for church, but it was just as common to find her out behind the house in the garden sweating under a wide blue sky, a broad brimmed straw hat, and a silk shirt splashed with brazen colors clashing in contrast to the hue of her pants. Perfectly garish.

My sisters and I quietly continued our work. Grabbing a shirt from the silky mound behind me, this one a deep emerald green I remembered how at Christmas she had once worn it with a pair earrings stuck through the collar her idea of “jazzing up” an ensemble. Ostentatious octogenarian that she was, we were cutting all of her shirts into quilt squares, though no one in the family, children or grandchildren, had ever made a quilt.

There were plenty of decisions surrounding her death that caused familial disagreement– her obituary, her headstone, her viewing. Most of these squabbles came from the amalgam of contrasting beliefs, values, views, and lifestyles manifest in her posterity. But everyone seemed to want to hold on to these shirts and other articles of clothing sometimes so threadbare, frayed, unraveling that only a few small quilt squares could be saved.

*(This is the latest in a series of essays here on Refined + Rugged. They include: Hope (Alaska), Hope (and Ice), Hope (and Earth), Hope (and Loss), Hope (and Love). I’m exploring what it means to be human in a time of unprecedented climate change. As the world warms, and humans begin and continue to adapt to these massive climate changes in our lifetime, what will this mean for our environment, our Earth, our children, and our grandchildren. As always, thank you for reading, commenting, liking, sharing, and generally pondering these questions with me. Love, Megan)