—–

Redolent waves of raw, hot pine tannin coursed across my senses in each trough of the trail. My bike and I undulated, at times, from below the root systems to the top of the bole of the Douglas Fir growing along most of the track. Pseudotsuga mensiesii, countless needles seemed to breath in unison in the softly rushing air from bark scabbed boughs to the tip of the tiny glimmering twigs into the understory all around me.

The loamy dirt still held some of the rain that had smattered over us just minutes ago, and then passed just as quickly as it had fallen. As we rode, I could see the soil was darkly composted with old leaves, myriad fir and pine needles. Light filtered through the blackened jade of each needle, twig, bough, and trunk, making shadows long and variegated across the trail.

The moment caught and held, pausing for a breath—one, two, three—sky, trees, breeze, light, earth, leaves. My gaze panned down the next switchback. I reminded myself to attend to the trail ahead of me rather than losing myself in the trees which might end in a disastrous fall. I trained all my focus again on my body, my rhythm, my flow. The rise and fall of the pedals, my eyes focusing two or three feet in front of me, intake of breath and exhalation, gear up for the rise, baby crest then pedal, pedal, gear down for the descent, flatten out my stance.

Churning out the miles I couldn’t help but repeat in my mind—here it is, this is it. It’s this kind of presence that makes human life palpable, enjoyable, full. But it may also be what keeps us from tackling major storms and stumbling on challenges that we face in life’s broader contexts. I am lucky. I can escape to the mountains whenever I please– cooler air, summer rains, mountain lakes, trails and more miles of trails. But so many humans do not have that luxury.

I thought of my boys at home. Thirty or so miles on the back side of the mountain I was ribboning down. They might be jumping on the trampoline, reading on the back patio, watching a Tik Tok on their beds. Their existence is often the perfect burr to return me to why I find climate change action important. In her article, “The Global Temperature Just Went Bump,” dated July 25, 2024, Zoë Schlanger explains that Sunday, July 21st was bested for “hottest day ever recorded on Earth” by the following twenty-four hours, Monday, July 22nd. The hottest day in 1,000 years… “since the peak of the last interglacial period, about 125,000 years ago.”1 Can you believe it? You, I, and my boys just lived it. Let’ s not hold our breath, kids, I’m certain we may see another record breaker this summer. Again, wild.

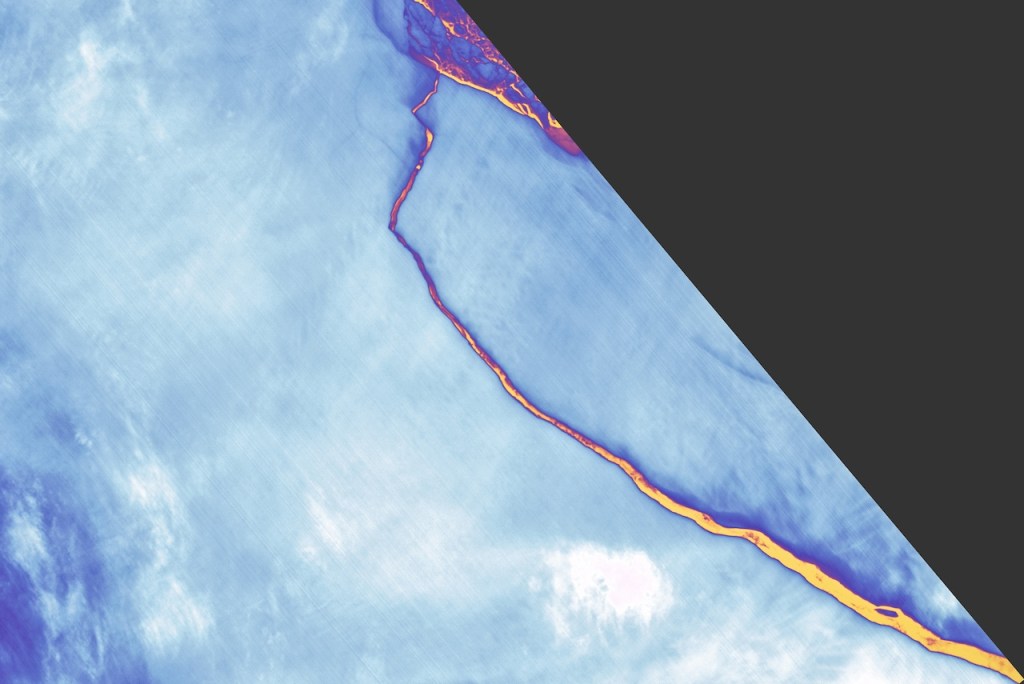

Maybe we, humanity, feels as though we’re ready to experience a warming period on earth that has been sped up to three times the last warming period. You know, like listening to an audio book on unintelligible chipmunk speed. Maybe we feel that we’re ready for hotter temperatures, more severe storms and weather patterns, shifting moisture bands, and a world that has very little Arctic or Antarctic ice. The impact that we have made on Earth’s climate have created climate shifts over 150 years that are closer to those that warmed the interglacial period Neanderthals experienced over several thousand years.

These scientific observations are mirrored in the human experience my boys and I are living, real-time in our quaint and un-airconditioned 1913 settler’s cabin (renovated, perhaps three different times). Our little home loves to rest in the heat at seventy-eight degrees. I can now tell you from a summer of experience that this ambient temperature is quite tolerable. For me, preferable to an office space frozen to 65 degrees while the outside temps tip towards the 100s. But still twenty or so degrees cooler than the ninety-eight to one hundred and six-degree days outside.

The boys and I are thick into the summer of a system of open windows, open blind louvers at night, queue the fans, open the whole house wide for the cooler nighttime air. Then reverse the process in the morning, at 7:30 a.m.—close the windows, shut the louvers on the blinds, keep the fans running, front porch full-sun in the morning, back porch a lovely ten degree drop at dusk. I think about the folks living in places like Phoenix, Tucson, Jacksonville, Charlottesville, New Orleans, Dallas, Houston, Death Valley, to name just a microcosm of the American cities that have experienced unprecedented heat waves this year.

What if I lived in a climate that never saw cool? What would I do if I were eighty and my air conditioner crapped out in this heat wave? From many folks’ perspectives, it doesn’t look good. George Packer, in a sweeping prospectus of Phoenix, one of America’s fastest growing cities, in his article titled “What Will Become of American Civilization?,” details the heat that killed 644 people last summer in Maricopa county for The Atlantic. Packer explains that those who pay the price for the heat really are the elderly, the mentally ill, the homeless, and “those too poor to own or fix or pay for air-conditioning, without which a dwelling can become unlivable within an hour.” I think of my boys trapped in a little house without AC in a desert without a way to cool down. What a tragedy.

The picture only appears more grim as Packer projects forward, “A scientific study published in May 2023 projected that a blackout during a five-day heat wave would kill nearly 1 percent of Phoenix’s population– about 13,000 people– and send 800,000 to emergency rooms.”2 Nearly one million heat stroked humans? Staggering. The situation even brings Packer a sense of shame that there is a 4,000 person waiting list for homeless persons who desperately want housing vouchers to get off of the street and out of the heat. Literally.

I’ve experienced my own micro shame at the warmth of my little house. Just yesterday I heard my youngest son speaking to his father on the phone, “Yeah, my room’s pretty warm. I’m okay.” I cringe a little and recognize that I’m also lucky enough to be able to install AC in my new-old abode if I were to choose to do so. It appears that from my children’s report, we may be contacting an air-conditioning company soon though my wish is to wait until next summer. I guess I’m willing to see what the next record breaking day feels like. Will my little home break 78 degrees? I may soon know. I’m certain if my boys get hot enough, they’ll also let me know. I’ll hear it from them.

—–

March 19, 2006. Many yesterdays ago, Logan, Utah. It’s early evening, one day before the official calendar date of Spring Equinox. Outside, snow falls through the dim blue haze of twilight. All across Cache Valley’s floor, the heavy wet flakes form standing pools with the slushy consistency of a 7-11 Slurpee. I’m inside writing. When things stop flowing on the page, I sink from the couch to the living room floor and piece together silk quilt squares from Grandma’s shirts, skirts, bathrobes, and mu-mu’s. Remembering is reflexive.

It’s a hard reality to face the fact that humans really have so little knowledge, perspective, or understanding of the future along their linear time-continuums. I didn’t know that the drive Grandma and I took in April 2005 would be our last. I look up from a neon square filled with exotic flowers that look like they’ve been bathed in black light and think back.

The sun’s spring angles were beginning to lengthen the days as I helped her into the passenger’s seat. Settling into the driver’s seat, I eased the car out of ‘park’ and pulled onto Highway 40 traveling Northeast. Warm breezes gently bent the tops of sage brush, bunch grass, paint brush, and river tamarisk.

Grandma asked me to roll down the windows even though she was dressed in long pants and a wool sweater to keep her shrinking frame from getting too cold. The wind flayed her gray curls like fingers, and my own hair whipped, unruly, this way and that. The smell of the baked red earth and burning sage made my teeth almost ache with the sweet biting iron odor. I didn’t know during that drive we were actually going to find hope. I was too young to understand.

Grandma carried an extra air of tired and confined energy about her. Eighty-one years and she was thin and ever thinner each time I’d visit. She had stopped working at the Mormon temple in Vernal each week, and she relied upon meals on wheels for lunch each day. She complained that she really couldn’t even taste the food that she ate. All this was portent of the end. But I returned my attention to the winding road, to the swell of the muddy Green River as it poured out into the sunshine through Split Mountain and the flicker of the leaves and the breeze in the trees around Josie’s cabin where we stopped to have lunch that day.

Once we were ready to leave, Grandma turned to me with an angelic smile and said simply, “Thank you. Today was lovely.” Loss is a funny thing. Often we lose things we love without warning. Standing at the passenger car door, helping Dorothy carefully out of her seat, her sweet hand in mine, I could never know it was the last time I would see her alive.

—–

OCEAN VUONG:

Oh, you know, you realize that grief is perhaps the last and final translation of love. And I think, you know, this is the last act of loving someone. And you realize that it will never end. You get to do this to translate this last act of love for the rest of your life. And so, you know, it’s– really, her absence is felt every day. But because I’m becoming an author again in another book, it is double felt.

And ever since I lost her. I felt that my life has been lived in only two days, if that makes any sense. You know, there’s the today, where she is not here, and then the vast and endless yesterday where she was, even though it’s been three years since. How many months and days? But I only see it in – with one demarcation. Two days– today without my mother, and yesterday, when she was alive. That’s all I see. That’s how I see my life now.

—–

—-

To reach the cemetery, I drive west across limestone plateaus which rise in graduated benches as Utah’s Great Basin climbs to meet the Uinta Mountains. The Mountain Home cemetery sits atop a ridge in the middle of farms of cattle and fields of alfalfa which are gradually greening on Easter Sunday 2006 as wheel lines rhythmically pulse water across field after field. When I am there, I hope she feels that she is home.

Grandma has two headstones. One slab of stone sits in the Manti, Utah cemetery, the other rests in Mountain Home, Utah. Her bones weren’t laid beside those of her third husband in Manti. Instead, her name, the short version– Dorothy A. Mickelson, is etched into the granite next to his– Clifton Christian Mickelson. I don’t think that her dates- birth or death- were blasted into Cliff’s headstone after she died. Her bones are buried here in Mountain Home. She said once, “I want to wake up among the gentle Farnsworths.” Her second husband’s people. How long will her bones lie there? One hundred years? Two? A millennia? More? I can’t tell.

There’s a kind of hope inked in Grandma’s big black scriptures. Maybe I will see it the way that Ezekiel describes, “there was a noise, and behold a shaking and the bones came together, bone to his [her] bone… lo, the sinews and the flesh came upon them, and the skin covered them… and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood up upon their feet…” Like, holy shit, an entire human being reconstituted, recombined, resurrected. Incredible. The description of resurrection from an ancient prophet once filled me with joy. But maybe her essence is already carried through the world on dust, atoms, mycelium, and pollen from the flowers and grasses that grow through the graveyard. Now Earth will boast Grandma’s stuff, the simulacra of her life carried on the wind through Mountain Home and the Uinta Mountains.

—-

Reverberation

by Megan DicksonIt’s impossible to feel alone soaking in the reverberation of humanity ringing through the great halls of civilization. The echo. The sound. The deconstructed interplay of all those expressions and explications bouncing and bounding around in the domed, arched architecture. Dancing over the simulacra, art, massive and tiny, representative of nothing and everything. The absolute alacrity the beatific joy of each repercussive utterance. Jazz. A fusion of improvisational auditory stimuli. The resounding transcendence of humanity in the envelope of a space. Astonishing.

—-

—-

Glacial recession obviously isn’t confined to Alaska or the poles. Even in Grand Teton National Park, the glacial retreat has been relatively well documented in the 19th century. It simply reminds me that no place on Earth will remain untouched by climate change. To our current understanding, there is no location where humans won’t experience the changes of the ever-warming earth. After hiking up some incredibly steep terrain with my sister a weekend ago, I can attest to how the heat affects humans in outdoor environments that used to be much cooler, even in the summer.

The hike itself up to Amphitheater Lake at 9, 850 some odd feet, is around 2,900 feet of elevation gain overall from the Teton Valley floor. The going is tough. Even for me, and I’m accustomed to life above 7-8,000 feet. I’ve go the lungs and legs for it, but this grade is brutal. The thing that drives you on when you hike is the peak. To reach the top. To look out over the many horizons you’ve melted. Up, up, and up we climbed. Not only did we want to reach the top, the gift was knowing that an icy glacier and snow-melt fed lake awaited us at our destination.

Up, up, and up the mountain. Jaw-droped and wide-eyed at the incredible crags, cliffs, arêtes, and sheer walls at the tipy-top of this incredible range. Mermaid–jump, dive, cool, swim. Down, down, down the mountain to a parking lot so hot that the waves of heat rise from the white gravel rocks making the horizon look like a circus mirror mirage. What does it all mean? The other reason to climb, hike, bike, or generally get outside is to leave the rush and pressure and unanswered questions of humanity behind.

To sync back into the rhythms of the Earth that have kept, housed, harbored, and nourished all life on this glorious planet for thousands upon thousands of years. Except this time, like a broken record, I can’t get the image of the recession of Teton Glacier out of my head. The reality is really ruining my vibe. Thought ridden, and wanting to focus on the moment, I pull off the narrow trail onto a rough patch of mountain meadow. I take deep cleansing breaths and remind myself that the answers humans need and seek from science, from sociology, from art, from politics, and from each other must be reached together– as a collective. When my personal understandings of how I can help to limit or roll back climate change become more clear, I will pivot. The simple wish is that humanity will have enough time to make changes in a world that seems perched on the precipice of climate disaster. Right now, all I can do is hope.

*This is the final essay in a series about climate change from one humble human perspective. The losses we stand to face in the future feel more real, more palpable each heated day of this record breaking climate summer– 2024. To my people: thank you for reading, liking commenting, and sharing. I am so grateful for the journey that writing creates– writer and reader in community together. You can read my other essays here on my website. Hope (Alaska), Hope (and Ice), Hope (and Earth), Hope (and Loss), Hope (and Love), Hope (and Fire), Hope (and Now).

—-