I stand near Hope, the muskeg path falls steep and spongy to the rhythmic, slate waves of Turnagain Arm. Gold, not ice, is what originally situated the town’s two hundred residents at the Northern root of the Kenai mountains in 1896. Now locals may be pondering which is more precious, or maybe the current answer is still ‘C’, “tourists.”

The first-green of fragile ferns springs up over dirt-peppered gobs of crusted snowmelt along either side of the trail. In the still-frozen snap of early May, birch bark flakes paper-white against the greywacke sandstone and granodiorite. Black and white spruce limbs and needles twine, their winter-fixed dance now a spring still life. Farther up the mountainside, an unseen breath of cool air wavers through the dark boughs of Lutz spruce posts, scrawny and more solitary.

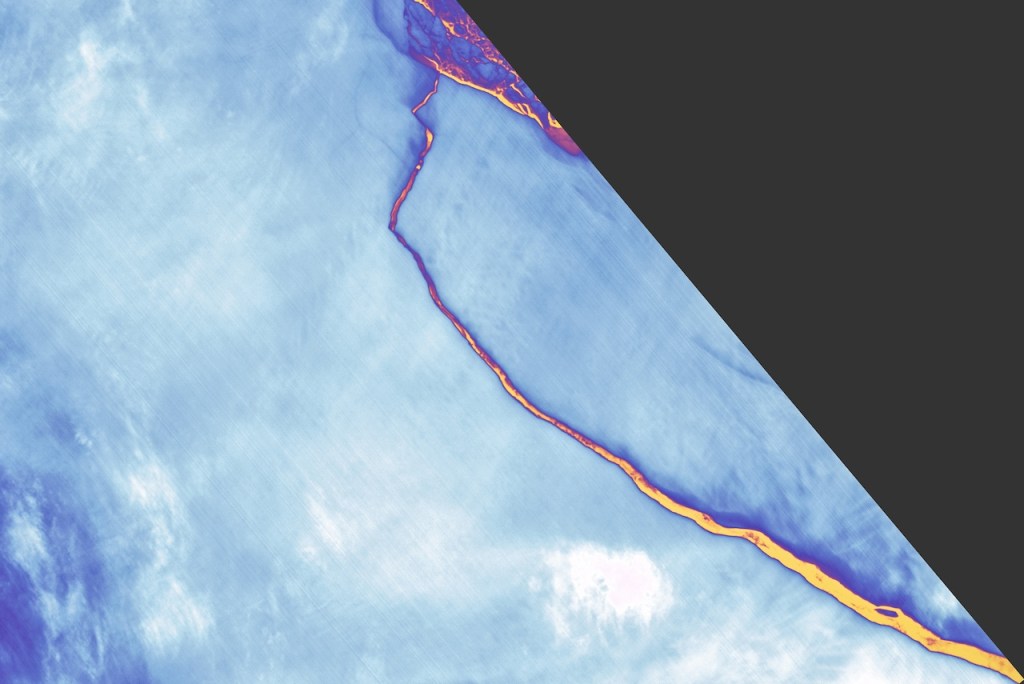

Hope and the rest of the Kenai Peninsula are divided from mainland Alaska by this choppy spume of Turnagain Arm. The watery arm is bounded by towering mountain ranges on either side—Chugach and Kenai. Seward Highway, one of the most scenic in the world, scratches its route out of Chugach bedrock on Turnagain Arm’s northern side. Standing on Turnagain’s southern shore, at the base of the Kenai Mountains, I look across the inlet.

The Cretaceous bulk of the Chugach, the parallel mountain range, sketches dark crags and cliffs into the northern horizon line as the contrast meets the dewy green iris of my eyes. Tall against the cerulean arc of the sky, the mountain’s ancient rocks remind me that I am young, barely twenty-one. Yet, I watch the world being born before me. Behind these mountains, small peaks protruded from blankets of fresh snow and ice like the breasts of rock Eves, nunataks, carved clean by this glacial ice. Creation isn’t finished here.

—–

Tenacious, tactless, and bursting with energy that can’t be contained in a somebody who’s seven, I was the kid who couldn’t be shut-down, shut-up, or put-out at a slumber party. Sticking my tongue through the enormous gap between my front teeth, I’d lay plans to stay up all night. First, I’d giggle raucously with my three other sleepover friends till ten. As the party started to die down, I’d begin the war if I could, two against two, two live-wires versus the two heavy-eyed and tired. Mercilessly I’d poke, prod, and pester our sleepy victims, sticking things up their noses and in their mouths, pelting them with jolly ranchers till midnight.

My co-terror would undoubtedly grow sleepy when I couldn’t dream up any more interesting battles to wage on the dreamers, and she’d drift off to dreamland herself. The war would wind down, and I’d remain alone and awake, watching creepy alien shows on the Sci-fi Channel. The living room floor seemed strewn with huge wriggling worms. Snoring seven-year-olds moaned and drooled and twisted into grotesque shapes which became part of the alien landscape all lit up by the TV’s fluorescent flicker. I’d be wide awake till dawn, and finally exhausted, fall asleep.

It’s this very same seven-year-old that Grandma Dorothy trots off with to Alaska in August of ’88 to visit her youngest son Bruce, and his family. Only Grandma didn’t just travel with one seven-year-old. That would have been too easy. Instead, she takes two. Flying on a jet-plane for the first time in our lives, my cousin Jenny and I can’t sit still for one moment of the five-hour flight. When we reach Anchorage, Alaska, we are reunited with a third cousin, seven-year-old Sarah. Grandma’s three babes. All girls, we were all born to Grandma in ’81 through her three sons—Ken, Floyd, Bruce.

It’s getting late, far past bedtime, probably nearing midnight Anchorage time. The three of us have been put to bed. I’m not tired. The black-out blinds in Sarah’s room, designed to keep out Alaska’s midnight sun, are framed in late summer light. To me, this isn’t night.

“Look, it’s not even dark,” I say.

“I know,” Jenny chimes.

“Does it ever get dark?” I ask Sarah.

“In the winter,” she replies.

We’re reading Charlie Brown comic books with a flashlight, trying to stifle our laughs with a pillow. One short comic strip makes us giggle till we’re red from burying our heads in the nylon folds of our sleeping bags. Charlie Brown and the gang are playing football. Charlie fumbles again and again, a complete failure, but Sarah, Jenny, and I don’t care. Realizing in retrospect that anything can be funny to three girls at age seven, it’s the one-liners that get us. This time it’s Linus. Holding his blanket and stumbling toward the fifty-yard line, he wants Charlie to pass him the ball. His arms raised high, his blanket trailing at his side, Linus yells, “Pass me the pig-skin, Sir!” Laughter grips our sides and cinches our lungs tight as we try desperately to snort air through our pillows. A floor above us, Sarah’s baby-sister Sophie starts to cry.

“Aw crap! We woke up Sophie,” I say.

Grandma’s voice shoots down the stair well, “Girls, go to bed.”

We’ve been caught, and our laughter dies. I settle into my sleeping bag, hoping for rest even though the light hasn’t died behind the blinds. The sun is still awake outside.

The next morning over breakfast, Uncle Bruce announces that we are all going to see Portage glacier. When the breakfast fiasco is done, we pile into their van and head out of Anchorage onto the Seward highway. We drive for a long child-time. Full-lunged, and over-dramatic, now we sing songs from all of our Broadway favorites. Then dissolve into rich peals of kid-laughter.

The incredible scenery passes unobserved by girls of seven who are content to chatter, giggle, and imagine with one another. Free from the van, we run headlong to the Visitor’s Center entrance in Portage Valley, unaware that with one glance toward the lake we could view the glacier face to face.

Inside, we are ushered into a movie theatre.

“What are we watching?” I whisper to Sarah.

“I don’t know,” she replies. The lights go dim.

“Quiet,” whispers Grandma.

The main screen cues and I read the title Voices from the Ice. The voice of the narrator begins its drone, and my eyelids threaten to become too heavy to rise. With a thundered, crumbling resound, an iceberg voices its descent from the glacier’s face and plunges toward the chunky melt water above the terminal moraine. I startle in my seat at the boom. Another massive chunk of ice calves off the front of the glacier and plummets into the lake. Now, fully awake, my senses are filled with wonder.

I ignore the commentary as the narrator’s monotone voice continues. Instead, I’m intent on watching Portage, one of over 600 named glaciers in Alaska, 30,000 estimated in total. These gargantuan ice mammoths gouge striations into rock, churn up sediment in track-like moraine. The scars left by the glacier remind me of the deep notches that appear in black pavement as cars scrape in and out of a parking lot entrance. Only these scars are not formed on soft blacktop but in granite bedrock as glaciers’ miles-thick arms of ice drag debris of all different sizes ranging from sediment, to pebbles, to boulders, on up to erratics– boulders the size of cars or small houses which glaciers ice-belt down mountainsides and across valley floors.

The camera pans from the expanse of snow across the ice field to a close-up shot of mesenchytraeus solifugus, a tiny indigo ice worm, as it wriggles through the structural holes in an individual ice crystal. What seems like a sterile chub of ice reveals life in microcosm.

I sit silent and still as the movie ends and the lights come up. The screen rises slowly to the ceiling, and the red curtain behind it parts. Real and a deep raw blue, Portage glacier rises from Portage Lake. The crystalline blue ice incongruously toes through pillowy gray skies. My breath fled. Before I know that glaciers are dying, with clean seven-year-old eyes, I am awed by ice for the first time.

—–

Encase: In Case

by Megan DicksonMelt me out, I’m not

going to make it in this

hostile environment

—–

There my sons are, jumping into a glacial lake for the first time. Bodies all bare and ready for the shocking cold. Running down the rocky shore so as not to lose resolve, they squeal into the water like little seals, a little less lithely. It’s like an exclamation point inside me. Grewingk Glacier’s lake is the swimming hole today, in Kachemak Bay State Park, Kenai Peninsula.

I couldn’t have dreamed up a more exciting family adventure. We’re here to celebrate my cousin, Sophie’s wedding, and it’s the first of many firsts for my boys in the ways of ice. My seven-year-old son holds up a puppy-sized, crystal clear chunk of glacial ice. His expression, open-mouthed awe. Just like I felt thirty years ago. Everything in me feels dazzled, just utterly magiced. A day really can glow and glitter in memory forever. This is wild.

—–

*(This is the first in a set of braided essays about ice, glaciers, Alaska, love, loss, and what climate change looks like at human-level.)